By Madeline Swanson | Photos provided by Marsal Family School of Education

As the bell rings at 8:30 a.m., a new day is beginning at The School at Marygrove, a first-of-its-kind K-12 public school on Detroit’s Northwest side that is part of the Detroit P-20 Partnership. Third-year teaching resident Anamaria Lopez (AM ’22, TeachCert ’22) is preparing her first graders for the “morning meeting.”

“We start with a greeting for everyone in the group, then we talk about what our schedule is for the day, we ask a sharing question, so they have a chance to share with each other—either something personal or academic—and finally, we do an activity,” she said.

Her passion for a teaching career dates back to childhood.

“Growing up, I didn’t have many teachers that were Latinx—I think I only had a handful of teachers, and even then, I don’t think that was until college,” Lopez said.

“I knew I wanted to be in education for the representation of people like me. I’m very proud of who I am and where I come from, and I knew that I wanted to be very community-based in my work, so teaching felt like the right profession for me.”

Lopez is joining the workforce at a time when teacher shortages are peaking. Addressing this crisis is a top priority at the Marsal Family School of Education, and during her graduate studies, she learned of a new model for supporting novice teachers.

In 2018, the Marsal School partnered with the Detroit Public Schools Community District, Starfish Family Services, the Marygrove Conservancy, and the Kresge Foundation to launch the P-20 Partnership—a cradle-to-career campus at the former Marygrove College in Detroit.

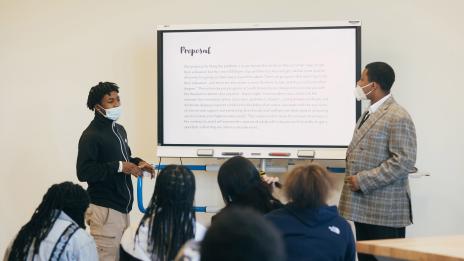

One highlight of the partnership is an extended teacher training program. Students at the Marsal School have the opportunity to pursue their teaching internship and student teaching through the school’s Michigan Education Teaching School at Marygrove. In a setting similar to a teaching hospital, all of the education professionals at the school have dual goals: children's rich and robust learning and the education of urban teaching professionals.

“I knew in my first few years of teaching it would be hard, but knowing that supporting us was a priority at Marygrove—that felt different,” Lopez said. “Having a U‑M mentor at Marygrove who’s there for you, without having to teach their own K-12 students, is phenomenal. I haven’t heard of that happening anywhere else.”

Students who complete an internship at the Teaching School are invited to apply for the residency program. As residents, newly certified teachers like Lopez are supported by experienced educators and Marsal School faculty and staff for three additional years—at no cost to residents. In addition to serving as certified members of Marygrove’s teaching staff, the residents also serve as near-peer mentors to interns still pursuing their degrees in teacher education at the Marsal School.

A couple hours later and after an English Language Arts lesson for Lopez’s students, it’s time for lunch and recess—a time for everyone to relax before the afternoon math lesson and recharge for the remainder of the day. Next up after math? A U‑M-designed curriculum in both social studies and STEM-based education.

“I think that’s one of the things that’s really revolutionary at Marygrove. We’re not teaching social studies the way social studies have always been taught,” Lopez said.

As early as kindergarten, students are learning about body positivity and respecting personal boundaries, the impact of community gardens and the effects of food insecurity, and more—education she calls “cutting-edge.”

“That’s what makes our education here go a step further than what I’ve seen at other schools. The curriculum is very honest and very loving because it’s based on what we see in the community,” Lopez said.

This holistic educational approach is already having an impact on students’ success. Whether it’s collaborating with the community garden on the Marygrove campus to help alleviate food deserts, or participating in “family visits” where youths and their families interact with teachers out in the community, students, and new teachers alike, are supported.

“Family visits give you an opportunity to have a relationship with parents and see how they engage with our scholars, because parents are always going to know their kids best. I’ve seen it lead to better attendance from students and it helps our relationship thrive in the classroom,” Lopez said.

Elizabeth Birr Moje, dean of the Marsal School and George Herbert Mead Collegiate Professor of Education, emphasized that supporting novice educators and promoting community-based educational systems is crucial to creating a pipeline of new teachers that are committed to remaining in the profession.

“This kind of support promises to increase the efficacy of novice teachers,” Moje said. “It’s a proof of concept of what can happen when community partners work together to provide superior educational experiences.”

As another school day winds down and students are picked up by their parents and guardians, Lopez reflects on the impact she hopes she’s having on her students as a budding educator in Detroit.

“I’m learning to hold my students to high standards and to be structured in my teaching so that they push themselves and know what they’re capable of,” she said.

“I want them to take all of these tools they’re getting from me and this school and go out and be changemakers.”