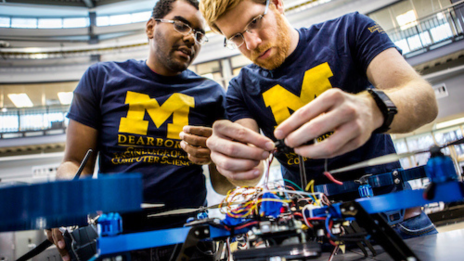

By Eric Gallippo | Photos by Marc-Grégor Campredon

Standing in front of a room full of students, Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Hafiz Malik studied two spectrograms to determine which snippet of audio featured a human voice and which was a machine doing the talking. To the untrained ear—and eye—it might be difficult to tell, but Malik has been working in audio authentication for 15 years and quickly spotted some major differences.

“If you look here, you can see the audio fades more gracefully,” he explained, pointing to the rise and fall of one graph. In the neighboring image, the lines were interrupted, representing chunks of data rather than the continuous energy flow found in human voices.

Malik’s skill at spotting so-called audio “deepfakes” has made him a favorite source for journalists looking to debunk bogus robocalls, viral social media clips, and other disinformation campaigns, especially in the run-up to the 2024 election. Last May, he was quoted at length in the Los Angeles Times about the risks posed by combining new artificial intelligence tools that make it possible for nearly anyone to generate convincing images, video, and audio and distribute them on unregulated social media platforms. Sitting in his office in the Tony England Engineering Lab Building at UM-Dearborn a month later, Malik gestured toward an inbox, frequently brimming with media requests, to indicate his summer plans.

To help handle the growing volume of deepfakes and the seriousness of the threat, Malik has been working with a team of students for the past year to develop a tool that would allow users to upload suspect audio through an online interface and run it through a series of tests to not only identify a fake, but also explain how it was detected. This second capability is not yet available. Malik hopes his team can ultimately train an artificial intelligence algorithm to do more of the lifting. For the foreseeable future, though, he believes humans still need to be involved in the process, as bad actors continue to develop new methods of degrading and distorting fakes to make them less detectable by even the leading software.

“We are trying to add different layers in the detection process by bringing in the emotions and looking at the energy flow and the change in pitch as we become emotional,” Malik said. “All those things actually flow through your vocal cords. The question is, ‘How can we tap into it?’ Yes, a machine-learning algorithm can be made, but that has to be done right, which is very difficult. It's not that you can use any architecture; bring it in, and it'll start doing the magic.”

Malik and his team are building a library of speech models for public figures—prominent politicians, celebrities, and other influencers—based on hundreds of hours of authentic recordings. The idea is to use them to analyze and compare to suspected deepfakes that could be used to sway public opinion, ruin reputations, or disrupt political campaigns. Last spring, hundreds of voters in New Hampshire received a prerecorded message claiming to be from President Joe Biden that encouraged them not to vote in the upcoming primary election. Malik determined it was fake after an Associated Press reporter sent him the message.

The implications extend beyond politics. As the COVID-19 vaccine became widely available in 2021, Malik said false rumors circulating about how the vaccine was developed raised concerns among many in the faith-based community, who turned to their leaders for guidance.

“If, as a faith person, you go to your clergy, you go to the rabbi or priest or imam and ask, ‘Hey, tell me, can I take the vaccine?’ Where can they go to get authentic information? Our goal was to create a system where they can go and put in their request and get information about some authentic sources, so that they can explain what is true. So this is one of the things, basically,

‘How can we protect society against disinformation, like a plague or pandemic, that we were in.’”

Hashim Ali, a Ph.D. candidate at UM-Dearborn studying electrical and computer engineering with a focus in audio forensics, is one of the students working with Malik. He recently published the results of a study on existing audio deepfake detectors and how their accuracy decreases as noises and other artifacts are added to the mix. Last year, Ali and others from his cohort did a study in response to College of Engineering findings that lasers can be embedded with audio information and used to activate speech-triggered smart devices, such as Amazon Alexa or Google Home. The goal was to identify differences between human speech and these laser attacks.

Keeping up with the news and cricket scores from his native Pakistan, Ali said it’s hard to know what’s real and what’s not on social media. In the past, hearing someone say the same thing as what he read gave it credibility. But that’s not necessarily true anymore.

“We live in an age where it's really easy to manipulate the content, very easy to lie about anything. And then, with these tools, they can help the lie; they can support the lie,” he said. “Fighting against the disinformation motivates me to push the technology ahead.”