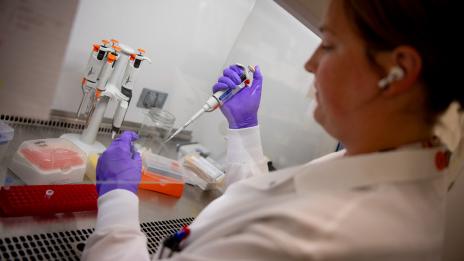

By Anissa Gabbara | Photos by University of Michigan School of Public Health, Shannon Schultz for Michigan Photography

The story below includes mention of firearm-related injury and death that readers may find distressing.

Once, it was simply a given that American schools were safe havens for students to learn and grow. Now, they are viewed as places where children are uniquely vulnerable to gun violence.

It’s a crisis that calls for action as mass shootings continue to plague schools and devastate communities nationwide—with 346 gun incidents in 2023 alone, according to the K-12 School Shooting Database. That’s why Justin Heinze (AB ’03, AM ’04), associate professor of health behavior and health education at the School of Public Health (SPH), is leading a U‑M effort to stem one of the most destructive epidemics of our time.

Reaching out

When four students were shot and killed at Oxford High School in Southeast Michigan on Nov. 30, 2021, Heinze went straight to work. As co-director of the SPH’s National Center for School Safety (NCSS), Heinze and his team reached out to schools in the Oxford area to provide expert-led training, technical assistance, and evidence-based resources to confront safety challenges.

These efforts were made possible by a $6 million award from the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) in 2019 to support STOP (Students, Teachers, and Officers Preventing) School Violence grantees and address student mental health issues resulting from school shootings. A more recent, $7.9 million three-year BJA grant is helping ensure NCSS’s services continue to be available to schools around the country.

Additionally, support from the Rodney W. Smith & Janet A. Kemink Fund for Firearm Injury Prevention through the SPH is aimed at providing under-resourced schools with the technical assistance they need to protect students.

“One of the opportunities that philanthropy has created is when there are school communities that have experienced a shooting or extreme violence, we can reach out to them and try to provide whatever support they need,” Heinze said. “Sometimes that is just, ‘Hey, we're here if you need us.’ Other times, it's thinking more specifically and intentionally about how we can create tailored resources to help students return to the classroom, to help support teachers who are trying to be educators but are also struggling with their own stress and trauma from an incident, or to help those communities around the affected community.”

Whether it's physical security, social-emotional learning, threat assessment, or mental health first aid, Heinze said that comprehensive planning can help address the range of school safety concerns.

“It's an unfortunate reality that, oftentimes, school safety conversations become the most salient after events like Oxford, but that's where we can be the most helpful to schools,” he added.

Making a difference with data

As Heinze noted, a number of school safety programs are not grounded in evidence. The efficacy of strategies such as active shooter drills or arming teachers in the classroom, for example, is unclear and can create a false sense of security or may even make students and staff feel less safe, he said.

As director of U‑M’s Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention’s school safety section, Heinze is co-leading the new Michigan School Safety Initiative. The effort involves a statewide needs assessment of schools, developing Michigan-specific safety resources and training, evaluating the efficacy and sustainability of current safety efforts, and leveraging a Michigan-based school safety advisory board. U‑M leaders are hoping that practices driven by the data gathered under the initiative will make classrooms across the state safer from mass shootings and other violent incidents.

“We prioritize programs and strategies that have been evaluated and have empirical findings supporting that, if they're implemented as intended with fidelity, they can make a difference in behavior- or violence-related outcomes,” Heinze explained.

‘A central priority’

The university’s efforts to address the gun violence epidemic extend well beyond the School of Public Health. As Heinze noted, faculty from Michigan Medicine; the School of Nursing; the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts; the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy; the Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design; and the Institute for Social Research are playing a role in addressing the crisis.

“The University of Michigan creates opportunities to draw from so many different areas of expertise to come together and think critically about designing, testing, and sustaining gun violence solutions,” Heinze said.

“U‑M is one of, if not the only institution that I can think of, that has made addressing the United States gun violence epidemic a central priority.”

As one of the world’s leading higher education institutions, U‑M is also in a position to prepare the next generation of leaders with tools to identify meaningful solutions to gun violence in Michigan schools and beyond. As Heinze noted, teaching students the value of evidence-based strategies—how to think critically about the data in front of them and make informed decisions—as well as making them aware of how gun violence impacts health equity in different communities can lead to positive outcomes.

“These are all pieces that I think U‑M is uniquely situated to do,” Heinze said. “We are built to support the people in the state of Michigan as well as the people in the United States—and even the rest of the world.”